Common SQL Mistakes in Oracle

Writing effective SQL is a critical skill for anyone working with an Oracle database. While SQL seems straightforward, a few common mistakes can lead to slow queries, incorrect results, and even catastrophic data loss. By understanding and avoiding these pitfalls, you can write more robust, efficient, and maintainable code.

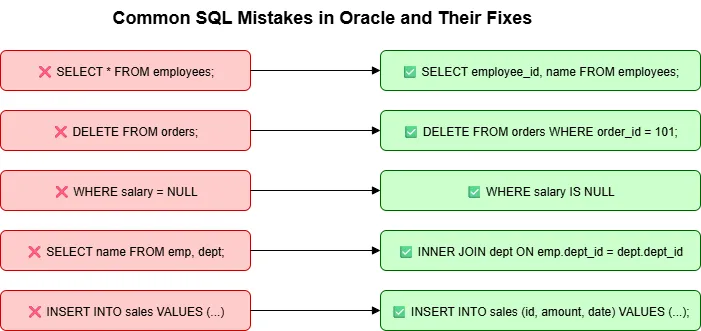

Here are some of the most frequent mistakes developers make in Oracle SQL.

Table of Contents

Mistake 2: Implicit Data Type Conversion

SQL Mistake 3: Mishandling NULL Values

SQL Mistake 4: Forgetting the WHERE Clause in UPDATE or DELETE

Mistake 5: Using Functions on Indexed Columns

Common SQL Mistakes 6: Using HAVING Instead of WHERE

Mistake 7: Relying on Implicit Row Ordering

Mistake 8: Overusing Correlated Subqueries

SQL Mistake 9: Inefficient Pagination with ROWNUM

SQL Mistake 10: Not Using ANSI JOIN Syntax

Common SQL Mistake 11: Unnecessary DISTINCT

Common SQL Mistake 12: Filtering Data in the Application Layer

SQL Mistake 13: Not Using Bind Variables

Common SQL Mistake 14: Confusing COUNT(*) with COUNT(column)

Common SQL Mistake 1: Overusing SELECT * in Production Code

Using SELECT * is convenient for ad-hoc queries, but it’s a bad practice in production applications.

Why it’s a mistake:

- Performance Overhead: Retrieving more data than needed leads to unnecessary I/O and network traffic.

- Code Fragility: If a column is added to the table, your application code might break.

- Index Issues: It can prevent the optimizer from using an “index-only” scan.

Bad Example:

--Fetching all columns when only the name and salary are needed

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 90;How to Avoid It: Always explicitly list the columns you need.

Good Example:

-- Fetching only the required columns

SELECT employee_id, first_name, last_name, salary

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 90;Mistake 2: Implicit Data Type Conversion

When you compare values of different data types (e.g., a VARCHAR2 to a NUMBER), Oracle performs an implicit conversion.

Why it’s a mistake: This conversion can prevent Oracle from using an index on the column being converted. If Oracle has to apply a function like TO_NUMBER() to every value in a column, it negates the index and forces a full table scan.

Bad Example: (Assume employee_id is a NUMBER column)

-- Comparing a NUMBER column to a string literal

SELECT first_name, last_name

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = '101'; -- '101' is a stringHow to Avoid It: Ensure that the data types in your comparisons match the column’s data type.

Good Example:

-- Using the correct numeric literal

SELECT first_name, last_name

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 101; -- 101 is a numberCommon SQL Mistake 3: Mishandling NULL Values

A NULL value represents an unknown value. A common mistake is to compare it using operators like = or !=. In SQL, NULL is not equal to anything, not even another NULL.

Why it’s a mistake: Any comparison to NULL using = or <> results in “unknown,” which is treated as false. Your query will not return the rows you are looking for.

Bad Example:

-- This will NOT return employees with no manager

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE manager_id = NULL;How to Avoid It: Always use the IS NULL or IS NOT NULL operators.

Good Example:

-- Correctly finding employees with no manager

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE manager_id IS NULL;Mistakes 4: Forgetting the WHERE Clause in UPDATE or DELETE

This is the most dangerous mistake. Omitting the WHERE clause applies the operation to every row in the table.

Why it’s a common sql mistakes: It leads to catastrophic, unintentional data loss.

Bad Example (The Nightmare Scenario):

DELETE FROM employees;How to Avoid It: Always double-check your UPDATE and DELETE statements. Best practice is to write a SELECT with the exact same WHERE clause first to verify you’re targeting the correct rows.

Good Example (Safe Practice):

-- 1. Verify which rows will be affected

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE hire_date < TO_DATE('2015-01-01', 'YYYY-MM-DD');

-- 2. Only after verification, run the DELETE

DELETE FROM employees WHERE hire_date < TO_DATE('2015-01-01', 'YYYY-MM-DD');

-- 3. Commit the transaction consciously

COMMIT;Common SQL Mistake 5: Using Functions on Indexed Columns

Applying a function like UPPER() or TRUNC() to a column in a WHERE clause can prevent Oracle from using a standard B-tree index on that column.

Why it’s a mistake: The database must calculate the function’s result for every row before comparing it, leading to a slow full table scan.

Bad Example: (Assume an index exists on hire_date)

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE TRUNC(hire_date) = TO_DATE('2018-06-17', 'YYYY-MM-DD');How to Avoid common SQL mistakes: Avoid wrapping the column in a function. Instead, apply logic to the other side of the operator. For cases where you must use a function, create a function-based index.

Good Example:

-- This allows the optimizer to use the index on hire_date

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE hire_date >= TO_DATE('2018-06-17', 'YYYY-MM-DD')

AND hire_date < TO_DATE('2018-06-18', 'YYYY-MM-DD');Common SQL Mistakes 6: Using HAVING Instead of WHERE

The WHERE clause filters rows before they are grouped by GROUP BY, while HAVING filters the groups after aggregation. Using HAVING for a task that WHERE can do is inefficient.

Why it’s a common SQL mistakes: The database has to group all the rows first and then discard many of them, which is more work than filtering them out beforehand.

Bad Example:

-- Inefficiently filtering after grouping

SELECT department_id, AVG(salary)

FROM employees

GROUP BY department_id

HAVING department_id = 90;How to Avoid this common SQL mistakes: Use WHERE to filter rows before aggregation. Use HAVING only for filtering based on an aggregate function (e.g., COUNT(*) > 10).

Good Example:

-- Efficiently filtering before grouping

SELECT department_id, AVG(salary)

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 90

GROUP BY department_id;Mistake 7: Relying on Implicit Row Ordering

A query without an ORDER BY clause does not guarantee any specific order for the results.

Why it’s a mistake: The order can change based on the execution plan, database version, or data changes. Code that relies on an implicit order is unreliable.

Bad Example:

-- This query might return rows in a different order each time

SELECT first_name, last_name FROM employees;How to Avoid this common SQL mistakes: If the order of rows matters, always explicitly state it with an ORDER BY clause.

Good Example:

-- Guarantees the results are sorted by last name, then first name

SELECT first_name, last_name

FROM employees

ORDER BY last_name, first_name;Common SQL Mistakes 8: Overusing Correlated Subqueries

A correlated subquery is a subquery that depends on the outer query for its values. It is executed once for every row processed by the outer query.

Why it’s a common SQL mistakes: This “row-by-row” execution can be extremely slow on large tables, a problem often referred to as “slow-by-slow” processing.

Bad Example:

-- Subquery runs for every single employee

SELECT e.first_name, e.last_name,

(SELECT d.department_name

FROM departments d

WHERE d.department_id = e.department_id) AS department_name

FROM employees e;How to Avoid this common SQL mistakes: You need to rewrite the query using a JOIN. JOINs are almost always more efficient as they process the data in sets.

Good Example:

-- The JOIN is processed as a single, set-based operation

SELECT e.first_name, e.last_name, d.department_name

FROM employees e,

departments d

WHERE e.department_id = d.department_id;Mistake 9: Inefficient Pagination with ROWNUM

A classic Oracle mistake is attempting to paginate results by using ROWNUM incorrectly in the WHERE clause.

Why it’s a common SQL mistakes: ROWNUM is assigned after the WHERE clause is evaluated. A condition like WHERE ROWNUM > 10 will never be true, because the first row returned is ROWNUM = 1, which fails the condition. No row will ever become ROWNUM = 10, so no rows are ever returned.

Bad Example:

-- This query will NEVER return any rows

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE ROWNUM > 10;How to Avoid this common SQL mistakes: For Oracle 12c and later, use the modern OFFSET FETCH syntax. For older versions, use a nested subquery.

Good Example (Oracle 12c+):

-- The modern, clean, and correct way

SELECT first_name, salary

FROM employees

ORDER BY salary DESC

OFFSET 10 ROWS FETCH NEXT 10 ROWS ONLY;Common SQL Mistakes 10: Not Using ANSI JOIN Syntax

Oracle supported a proprietary comma-based syntax for joins for many years. While it still works, the modern ANSI SQL JOIN syntax is superior.

Why it’s a mistake: The old syntax is harder to read, and it’s easy to accidentally create a Cartesian product by forgetting a join condition in the WHERE clause. The syntax for outer joins ((+)) is also confusing.

Bad Example (Old Syntax):

-- Harder to read and error-prone

SELECT e.first_name, d.department_name

FROM employees e, departments d

WHERE e.department_id = d.department_id(+);How to Avoid It: Adopt the modern, explicit ANSI JOIN syntax.

Good Example (ANSI Syntax):

-- Clear, explicit, and standard

SELECT e.first_name, d.department_name

FROM employees e

LEFT JOIN departments d ON e.department_id = d.department_id;Common SQL Mistake 11: Unnecessary DISTINCT

Adding DISTINCT to a query is sometimes used as a quick fix to remove duplicate rows, but it comes with a high performance cost.

Why it’s a mistake: DISTINCT forces the database to perform a sort or hash operation on the entire result set to identify duplicates. It often hides an underlying problem in your JOIN logic that is producing the duplicates in the first place.

Bad Example:

-- Using DISTINCT to hide the fact that the join to job_history creates duplicates

SELECT DISTINCT e.employee_id, e.first_name

FROM employees e

JOIN job_history j ON e.employee_id = j.employee_id;How to Avoid It: Analyze your joins to understand why duplicates are appearing. If you only need to check for existence, use an EXISTS subquery, which is far more efficient.

Good Example:

-- Using EXISTS to find employees who have a job history, without creating duplicates

SELECT e.employee_id, e.first_name

FROM employees e

WHERE EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM job_history j

WHERE j.employee_id = e.employee_id

);Common SQL Mistake 12: Filtering Data in the Application Layer

A common anti-pattern is to pull a large dataset from the database and then filter it in the application code (e.g., Python, Java).

Why it’s a mistake: It wastes network bandwidth, consumes excessive memory in your application, and ignores the fact that the database is highly optimized for filtering data.

Bad Example (Conceptual):

- Run SELECT * FROM employees; in the application.

- In the Java/Python code, loop through thousands of results to find the 5 employees in department_id = 50.

How to Avoid It: Let the database do the work. Push all filtering logic into the WHERE clause.

Good Example:

-- The database efficiently finds and returns only the 5 rows you need

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE department_id = 50;Common SQL Mistake 13: Not Using Bind Variables

When executing the same statement multiple times with different values, many developers concatenate the values directly into the SQL string.

Why it’s a mistake: Each unique SQL string forces Oracle to perform a “hard parse,” which is a resource-intensive operation to check syntax, semantics, and create an execution plan. Using bind variables allows Oracle to parse the statement once and reuse the execution plan for subsequent executions (a “soft parse”).

Bad Example (in Application Code): A loop generating these separate statements:

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE employee_id = 101;

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE employee_id = 102;

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE employee_id = 103;How to Avoid It: Use prepared statements and bind variables in your application code.

Good Example (Using a Placeholder):

-- The statement is parsed once

SELECT * FROM employees WHERE employee_id = :id;

-- The application then binds different values (101, 102, 103) to :id for each executionCommon SQL Mistake 14: Confusing COUNT(*) with COUNT(column)

These two functions serve different purposes. COUNT(*) counts the total number of rows, while COUNT(column) counts the number of rows where column has a non-NULL value.

Why it’s a mistake: Using COUNT(column) when you intend to count all rows can give you an incorrect result if that column contains NULLs.

Bad Example: (This will give an incorrect total if any employee has a NULL commission)

-- Incorrectly trying to count all employees

SELECT COUNT(commission_pct) FROM employees;How to Avoid It: Use COUNT(*) to count all rows in a table or group. It is the standard and most efficient way. Use COUNT(column) only when you specifically need to count non-NULL entries for that column.

Good Example:

-- Correctly counts every employee

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM employees;Common SQL Mistake 15: Using IN with a Very Large List

Using an IN clause with a long list of literal values can lead to poor performance and parsing issues.

Why it’s a mistake: Oracle may struggle to optimize a query with hundreds or thousands of values in an IN list. The SQL statement itself becomes very long and can be inefficient to parse.

Bad Example:

-- This can be slow and hard to manage

SELECT *

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id IN (101, 102, 103, /* ... 2000 more IDs ... */);How to Avoid It: For large lists, load the values into a global temporary table and rewrite the query as a JOIN.

Good Example:

-- 1. Insert your list of IDs into a temporary table

INSERT INTO my_temp_ids VALUES (101);

INSERT INTO my_temp_ids VALUES (102);

...

-- 2. Join to the temporary table

SELECT e.*

FROM employees e

JOIN my_temp_ids t ON e.employee_id = t.id;Common SQL Mistake 16: Ignoring Execution Plans

The most critical mistake of all is writing SQL and never checking how the database actually executes it.

Why it’s a mistake: The execution plan is Oracle’s roadmap for running your query. It tells you if you are using indexes, what type of joins are being performed, and where the costs are. Ignoring it means you are flying blind when it comes to performance.

How to Avoid It: Learn to generate and read a basic execution plan. In tools like SQL Developer or Toad, you can simply press a button (often F10 or F5). Look for red flags like a TABLE ACCESS FULL on a large table where you expected an index scan. Analyzing the plan is the first step to tuning any slow query.

How to access live SQL for validation

You can use Oracle Live SQL for validating the SQL without having any access to real databsse.

Conclusion

SQL mistakes are easy to make but costly to fix. By avoiding these common pitfalls—like using SELECT *, ignoring NULLs, or forgetting a WHERE clause—you’ll save debugging time, improve performance, and ensure data integrity. Always use a good sql editor for better query.

Key Takeaways:

- Always be explicit in your queries.

- Handle NULL values carefully.

- Use joins wisely and avoid unnecessary subqueries.

- Secure your queries with bind variables.

- Commit or rollback transactions promptly.

👉 Following these best practices will make your Oracle SQL queries faster, safer, and more reliable.

Pingback: Top SQL Queries Asked in Interview in Oracle R12